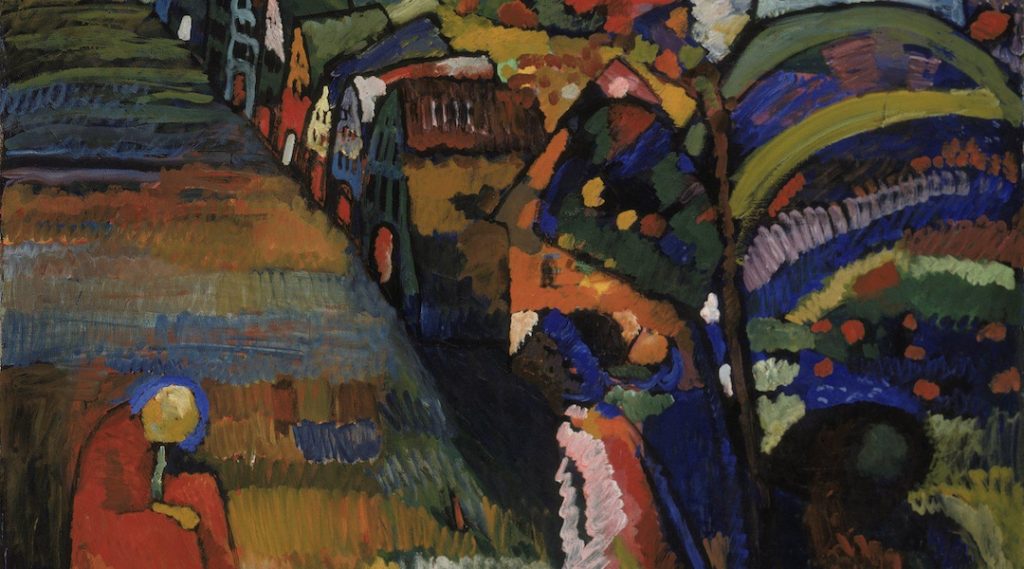

Irma Klein sold “Painting with Houses” by Wassily Kandinsky during the Holocaust. (Courtesy of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam)

Following a protracted legal fight, the family of Irma Klein last year finally got Dutch restitution officials to recognize that the Nazi occupation forced Klein to sell her Wassily Kandinsky painting to this city’s municipal Stedelijk Museum for a fraction of its worth.

That was in 1940, several months into the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, when Klein and her husband sold “Painting with Houses” for the modern-day equivalent of about $1,600 because they needed money to survive the Holocaust.

In its ruling last November, the Dutch Restitutions Committee accepted the family’s account.

But in an unusual and controversial departure from universal practices, the committee also determined that the painting should not be returned to the family. It cited “public interest” in keeping the work on display at the Stedelijk, among other arguments.

It was the latest of several such refusals by the Netherlands based on what the Dutch Restitutions Committee introduced in 2013 as a “weighted interest” approach to looted art.

It has prompted outrage and concern by some experts, claimants and their representatives. They fear a precedent and see injustice by a country that used to be considered a model implementer of art restitution practices.

“These developments risk turning the Netherlands from a leader in art restitution to a pariah,” Anne Webber and Wesley Fisher wrote in a December op-ed in the Dutch daily NRC Hadelsblad. Webber is an art restitution expert and Fisher is the director of research for the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. Their essay was titled “It’s a scandal that this stolen art hangs at the museum.”

It is “particularly disturbing,” Fisher told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, that this is happening in the Netherlands, which is one of only five countries (the others being Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom and France) that set up committees to determine the provenance of suspect artworks. Such committees were a key requirement of the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art – a landmark document agreed upon in 1998 by 44 countries.